Tales of Zestiria and Fairy Fencer F: Spot the Ten Differences

News of the hour: all Japanese role-playing games are the same.

This medal for successful multi-year cloning of video games has, believe it or not, two sides. The first one is visible when designers start trying hard and stringing interesting new things like a twisted plot, original setting, or some unusual mechanics onto a decades-old grind with a bunch of numbers. I remember once they put a whole Harvest Moon on our endless dungeons with slimes and colorful salamanders. Several times in a row.

Those were the times.

Nowadays, we seem to be looking more at the opposite side. I don’t even know how to call it. If we remember the Deep Soul of Japanese games and put on a serious, pompous face, we can say that many studios are currently experiencing an ideas crisis and so on. But somehow it feels more like these studios have simply surrendered to autopilot, and until a well-known rooster pecks them to death, they don’t intend to move.

As a visual example, I will give you two games. The first one is Tales of Zestiria, a continuation of a widely known RPG series, an anticipated genre novelty of October. The second one is Fairy Fencer F, a budget creation of an unknown studio, sold on Steam for 200 wooden coins.

ToZ and FFF – two identical games. Down to the smallest details.

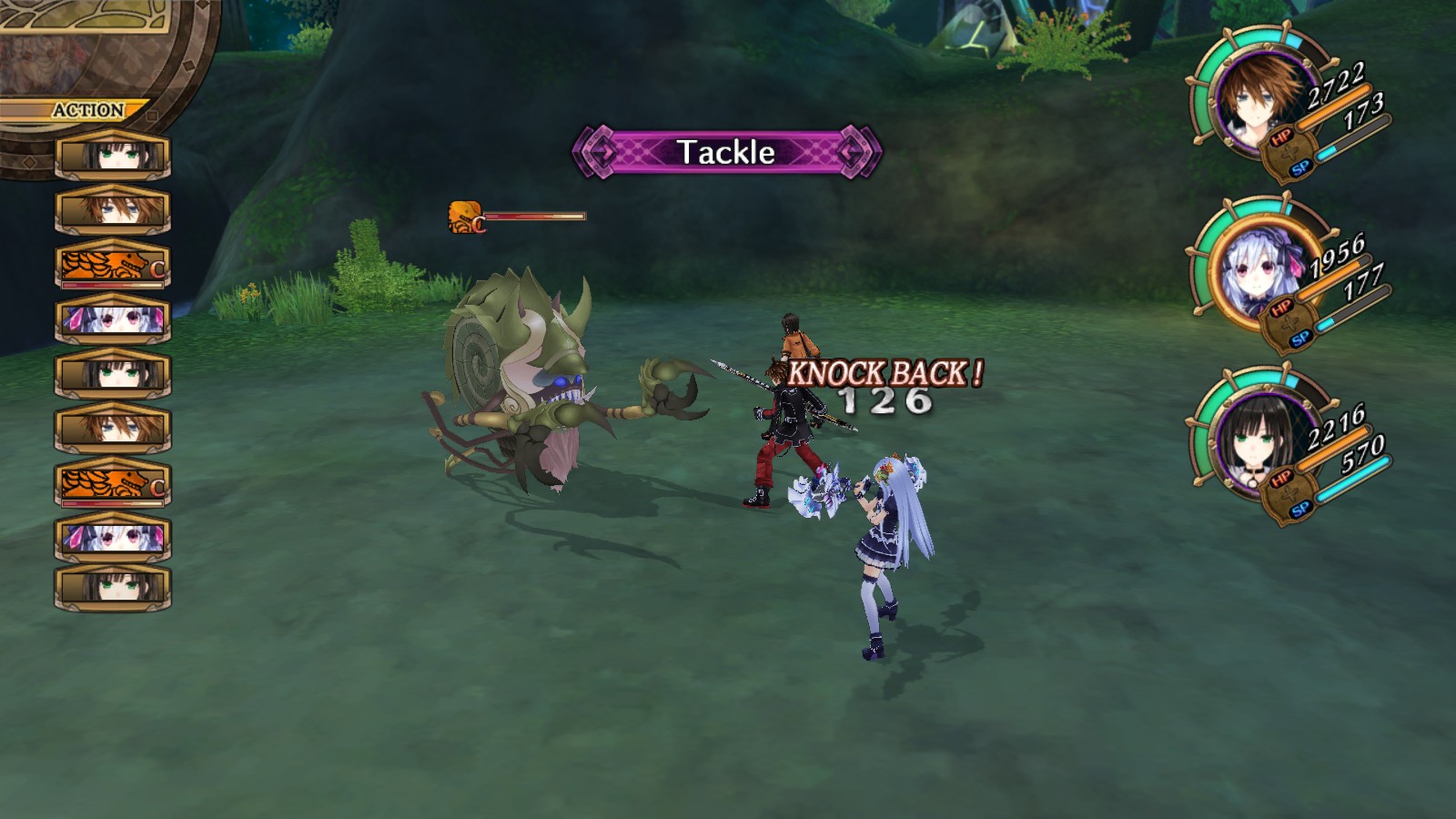

This, if anything, is Fairy Fencer F.

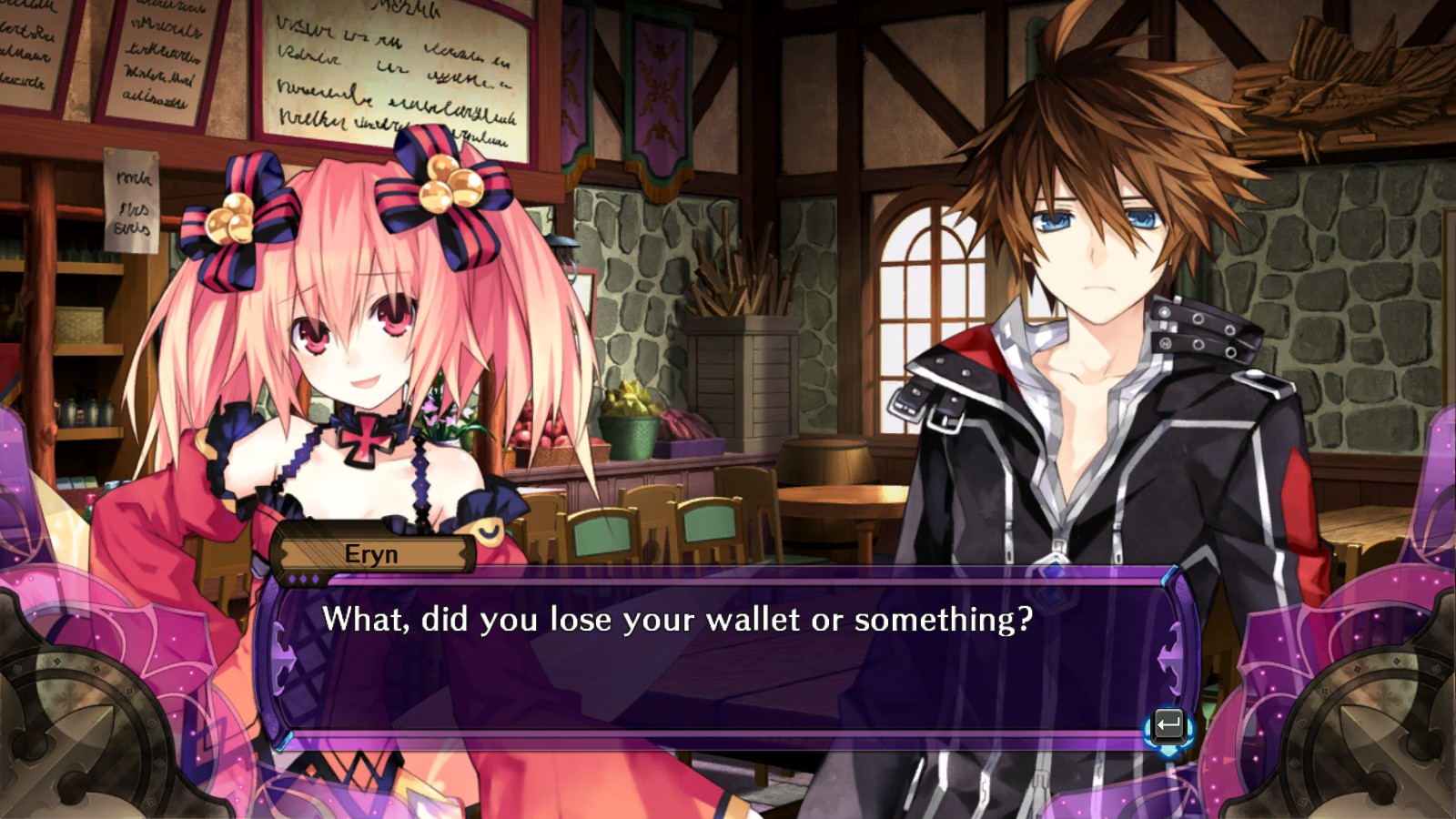

And this is also Fairy Fencer F, but with graphics. I mean, this is Tales of Zestiria.

Plots: in a relatively fantasy world built on the ruins of an ancient civilization, humans and magical spirits coexist. Since FFF is low-budget, these spirits are simply called fairies; ToZ, on the other hand, works with a bigger budget and refers to its magical people as seraphim. The world seems to be living its own life, but evil lurks everywhere, so our main hero needs to gather a company of local elves and people from all backgrounds and awaken the Great Good in both cases. However, in both worlds, there is a shady knowledge that wants to subjugate the Great Good. But, of course, everything is not so simple, and behind the facade of obvious opponents lies something greater, ancient, and terrifying.

Both games don’t particularly bother with enticing the gamer into their entertaining worlds, relying more on their own enthusiasm. Well, like, since you came, here’s a kind teenage princess with a spear and a desire to do good, here’s an archaeologist with a big bust and an irresistible desire to take off her clothes, and everyone around wants to be your friend and go to hell with you. And, most importantly, they mostly approach you themselves and say, “Let’s be friends!”

The plot with some money.

Naturally, morning events of love and friendship are constantly interrupted by sudden episodes of “Children under 16”, behind which you can clearly see the faces of artists who drew short skirts and non-childish forms, sighing “Well, you want it yourself” and day after day drawing combat swimsuits. For a dozen different identical projects.

Because Grindan calls.

In general, the Tales of series is supposed to be significantly different from the others in terms of combat. While competitors are conditionally divided into two camps (let’s call them “Team Phantasy Star” and “Team Final Fantasy”), Tales of, since the time of the SNES, has made its combat system similar to fighting games and other beat’em-ups. The opening, of course, will show that we still have a representative of the second group, but in Tales of Zestiria, you can really run and jump during fights. Fairy Fencer F, on the other hand, honestly plays out a turn-based map.

At the same time, our experimental couple, like gymnasts-synchronizers, in unison emphasize the mechanics of merging heroes with fairies/seraphim. Like, this way they fight better. And both RPGs want gamers to pre-set various combos, which in turn must be tailored to different types of monsters. For this, in both games, you need to grind separate combo move points. And also, at the same time, answer the question of why not just hang something universal like “hit-hit-hit-hit”, instead of using magic on unusual opponents and bosses with puzzles for the correct combat algorithm?

In practice, these two seemingly different systems work on the same idea. We simply click on ordinary monsters (in Fairy Fencer F, you need to hit the keys to save time and avoid the wasted five-second animations embedded in the moves, in Tales of Zestiria – so that our hero does not stop waving his wooden sharpener), and for serious opponents, we delve into the magic menu and possibly spend on combat merging.

The plot, with less money.

Do you know how to get the most pleasure from hours of monotonous grinding? Well, when the secrets of mechanics are mastered, and after each fight you want to see the experience bar crawling, you need to take a deep breath and stay at the current location for about twenty minutes. Better yet, thirty. It’s really cool if you beat the monsters to the point where they can’t give you more than 1 experience point after the battle, but that’s for complete masochists.

The reward for diligence will be waiting for you at the end of the dungeon, with the story boss. Spoilers for both games: in eleven out of ten important historical fights, a little devil will jump out of a snuffbox, which you won’t be able to defeat until someone from your party finds New Powers according to the scenario, or an Unexpected Ally comes to help. And so, the game expects that by the third turn, the protagonists will be well equipped, but in reality, they have already practically defeated the villain. But the scripts and the plot cannot be canceled just like that, so our heroes have to break the comedy, pretend to be victims, and wait for salvation from a third party, suddenly predictably jumping out from around the corner and flexing their muscles three levels lower than ours. The joke works flawlessly, for several dozen hours, in both projects.

Playing such games in one go is difficult, but if you know the measure and love Japanese role-playing games, neither FFF nor ToZ will disappoint. They diligently recreated every first genre cliché for a reason.

There is nothing truly original in our two games. Tales of Zestiria is a bit more embellished – voice actors don’t slack off, there are more details of virtual life in ToZ (for example, local heroes have learned to brew potions on cooldown, which is pleasing), and they show a cartoon in the opening. But overall, both FFF and ToZ are a set of dungeons with simple boss puzzles and attached cardboard puppet theaters. Fairy Fencer is a bit more vulgar, Zestiria is a bit more pompous.

What I like about Fairy Fencer F is all the menus and the map. That’s where the soul is!

Neither Fairy Fencer F nor Tales of Zestiria know what it’s like to be controlled with a keyboard and mouse. The developers of the latter seem to have been able to afford tickets to the Tokyo Game Show and spent about fifteen minutes watching how Western designers handle things. But it seems they were still looking at a console project, so we’ll still have to navigate all the menus and options with arrow keys, Page Up/Down, Caps Lock, and more.

I don’t want to hear anything about console ports, and I’m not going to thank anyone for the fact that these ports exist at all. This nonsense has been going on for decades.

**

The main difference that your humble servant noticed between FFF and ToZ is the price tags. It’s hard to say whether it’s a compliment to the former or a reproach to the latter. They both seem rather generic, you know. It seems that there’s a shortage of original ideas in the East right now.

We’re waiting and hoping for the next Persona, but in the case of successful sales, we’ll play Fairy Fencer F and Tales of Zestiria.

Share

Discuss

More Reviews