Beyond: Two Souls Review

In Beyond: Two Souls, you will have to deal with things that are quite unusual for video games. You will control a small, frightened girl as she hugs her toy and tries to ward off nightmares. You will decide whether she should drink beer at an uncomfortable teenage party and try to pick music that will impress the older kids. You will clean the house before a date and choose the right moment for a kiss.

And then, for a solid hour, you will hide in the shadows, taking out guards in a mission to assassinate a Somali dictator. However, if we are from the same test, you will quickly want to return to the uncomfortable party.

In popular games, there is rarely an opportunity to engage in something mundane. They are more focused on something extraordinary and exciting – incredible adventures, brutal wars, daring escapes – they ignore everything that players do in their everyday lives. But even as background, such details bring something fresh to blockbusters and are surprisingly enjoyable. Beyond: Two Souls succeeds – and fails – in trying to balance between these two extremes.

The best description for Beyond is a “cinematic quest”. The game tells the story of Jodie Holmes, a young girl with supernatural powers, played by actress Ellen Page, known for her roles in the movies “Juno” and “Hard Candy”. Jodie possesses paranormal abilities that manifest through Aiden, a mysterious invisible spirit mysteriously connected to the girl. For as long as Jodie can remember, she constantly feels his inexplicable and sometimes dangerous presence, and, with a few exceptions, the entity obeys her will.

Beyond: Two Souls is an ambiguous game. There are almost as many successful moments here as there are failures. It will definitely appeal to calm and unbiased individuals, but it will also clearly provoke indignant contempt from an equal number of other players. I recommend playing it, but I definitely wouldn’t recommend it to everyone.

The story jumps forward, backward, and forward again over a span of 15 years in Jodie’s life, from her first childhood impressions at 9 years old to risky adventures at 24. Here she is at 20, hiding from the police in a dried-up desert, and here she is again – a scared little girl living in a government research facility. Sometimes mystical moments from the future are explained by flashbacks from Jodie’s childhood and vice versa. All of this is presented very pretentiously.

Beyond is the brainchild of French writer/director David Cage, known for his experimental games Omikron: The Nomad Soul, Indigo Prophecy, and Heavy Rain. Nowadays, Cage is widely known for his admiration of Hollywood and his belief that games should “reach a new level.”

Cage’s Hollywood worship is fully manifested in Beyond – this game resembles a fantastical TV series that inexplicably requires viewer intervention. The player’s activity here is reduced to such an extent that all the merits and flaws depend entirely on the plot, which can’t be called bad, but it doesn’t live up to expectations. The irony of Beyond is that it elegantly and realistically demonstrates the emotional nuances of Jodie’s transition into adulthood, but at the same time, it gets stuck in adolescence – between childish staged spectacles reminiscent of various Call of Duty games and the sophisticated creations of the best game scriptwriters.

In addition to Aiden – who doesn’t speak and communicates with Jodie through strange ghostly sounds – there is another constant figure in the girl’s life, government agent Nathan Dawkins. His role is played by Willem Dafoe himself, who educates and raises Jodie for most of her life. Their relationship plays a decisive (though not sufficiently developed) role in the narrative structure.

The actors have settled into their roles well, with Paige, in particular, doing better than ever in working with material that sometimes looks charming, but its clichés become more and more noticeable.

It’s hard for me to blame Jodie for her excessive depression – after all, her life wasn’t a series of pony rides and pajama parties – but I would like to see more of Paige’s natural charm. Partly to blame here is the motion capture technology that Cage calls the future of game dramaturgy but still can’t quite handle the “uncanny valley” effect. Characters (including Jodie) speak like ventriloquists – their lower lips move, but the rest of their faces remain motionless.

Sometimes players are offered dialogue options that work on the principle of other Cage games. Instead of specific Jodie’s lines, players are given lines like Lie/Tell the truth/Dodge the question, Thoughtfully/Aggressively/Threateningly, and similar. The narrative, focused on flashbacks, makes such choices not very obvious – at first, I simply didn’t know how Jodie would act in a particular situation. And how could I know? The game has just started, and chronologically Jodie’s story is approaching the middle.

The game is clearly designed so that people who don’t play regular games can quickly get used to it – the controls, already simplified in Heavy Rain, have become even simpler. A couple of buttons on the controller are enough to play the game, and it can even be controlled from the touchscreen of a smartphone.

Each gameplay action requires minimal intervention from the player. You wander around the location using the left stick, and click on interactive objects marked with a white dot using the right stick. You almost never tell Jodie what exactly she should do with them – she will decide for herself. Maybe she will play the guitar or read a document or open a door – for the vast majority of such actions, you just need to click the right stick.

Throughout the story, Jodie becomes an experienced close combat fighter (one of the silly joys in Beyond is watching the tiny Ellen Page take down guys twice her size, one after another). When a fight begins, time slows down every time Jodie needs to duck or dodge, and at that moment, you should move the stick in the direction she is moving. If you don’t do it in time, she will miss a strike or won’t be able to perform an attack, but it won’t have much impact on the outcome of the fight.

Compared to Jodie, Aiden has more freedom of action – apparently, these are the advantages of incorporeal beings. The triangle button on the PS3 allows him to leave his body and fly through walls, scout the area, and drop or break something.

But despite the ability to control an immaterial entity, Beyond still feels claustrophobically tight. Partly because the game and its world do not burden themselves with unshakable rules. Sometimes Aiden can drift away from Jodie for almost a hundred meters, and other times – when the plot requires it – the leash is shortened to a few steps. Most enemies are immune to Aiden’s abilities, but in some, you can possess them, and in others, you can kill them on the spot. Most of the time, players can freely control Aiden, but sometimes this option is not available. There is no consistency or clear reason for this – everything is simply strictly dictated by the plot. Such inconsistency eliminates any weak sense of involvement in the game that could have arisen in the player. By offering players the illusion of control over what is happening and delivering it on a schedule, the game confines them within narrow boundaries and seems to constantly do them a favor.

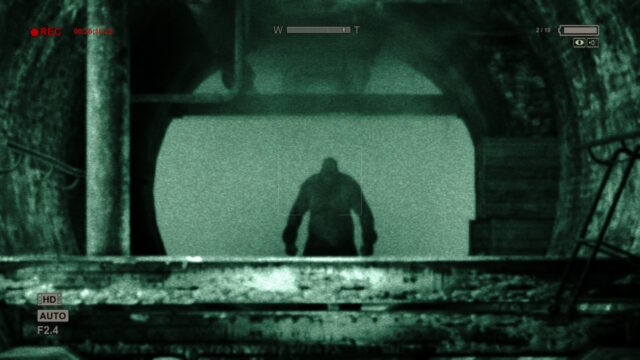

The worst moment in Beyond is the drawn-out stealth mission in Somalia, where Jodie, working for the CIA, is tasked with eliminating a local dictator. The plot is banal, the action is uninteresting, and clichés abound everywhere. And on top of that, the local design is very strange. When Jodie approaches another group of enemies, the obvious scripted path they will take becomes immediately clear. You know stealth where there are no rules and you can’t make a mistake? Here it is. It’s like a person who has never played Metal Gear Solid 4 dreaming about playing Metal Gear Solid 4.

Death or any other catastrophic failure is fundamentally absent. Leave Jodie hanging in a life-threatening situation, and she will either save herself or the game will wait until you do. In Heavy Rain, there were moments when the main character could die – the story would continue, but the ending would be completely different. Jodie cannot die in Beyond, and none of the decisions you make will significantly affect the ending. One plus here is that you don’t feel the burden of responsibility – you simply choose one of the options and confidently move forward, knowing that nothing will change in the game.

Perhaps it is the fragmented narrative that makes the insignificant episodes unexpectedly enjoyable. After all sacrifices have been made, all children saved, and all tears shed, you can enjoy simple moments from Jodie’s everyday life that actually look interesting. I especially like the preparation for a sudden date: the young man Jodie is interested in will arrive within an hour. Her house is a mess. Will you manage to clean up in time, prepare lunch, and take a shower? And what about Aiden, who is angry and jealous of the new admirer?

And what should Jodie wear?

It’s an unusually captivating hustle and bustle, and everything becomes even more interesting during the actual date. The awkwardness experienced by both characters is very realistic, their communication is filled with sharp changes of topic and hesitant questions that anyone who has been on an exciting first date knows all too well. Actors feel most comfortable in such everyday situations, and the whole performance is perceived with enthusiasm. Cage says that games need to reach a new level, to abandon explosions, violence, and absurd scenarios from action movies – and in scenes like these, he demonstrates his ideas in practice.

And it’s even more nauseating that he stuffed his game with those very explosions, violence, and absurd plot devices. Overall, the story in the game is quite good, but at times it is so shamelessly banal that it is difficult to take it seriously. And worst of all, Beyond failed to become a game about something specific. Among all its inspiring moments, I couldn’t find a proper unifying idea. “Ghosts are scary,” maybe.

The plot is a mishmash of “The Sixth Sense,” “Ghost,” cheap movies about the X-Men, and even “Final Fantasy.” Cage never misses an opportunity to insert clichés – in one scene, a character hits his commander and says, “Consider this my resignation statement!”

Other gems from the dialogue: a villain, frightened by Aiden, says, “Some kind of spirit has come to punish us for our sins!”; Willem Dafoe with a stone face says, “Infraworld will continue to spread further in our dimension!”; Jodie, gracefully leaving her colleagues, says, “I’m going out. I need to pee, I have no strength.” The Coen brothers never dreamed of such things.

In its best moments, Beyond: Two Souls tells the story of the coming-of-age of a strange young girl with an unusual gift. Many wonderful games like Cart Life, Persona, and Papers, Please show us everyday life from new perspectives. And when Beyond, like Heavy Rain before it, boldly relies on a generous budget in such risky creative approaches, it is doubly disheartening to see the clichés of Hollywood action movies in it.

Nevertheless, I still recommend it to you. Considering all its merits as a hybrid of film and game, Beyond: Two Souls will easily help you have a pleasant time. In co-op mode, it truly shines – one player as Jodie, the other as Aiden, and both can interact with the world, make important decisions, and immerse themselves in the story together. It is far from the worst way to spend a few evenings with a loved one.

Beyond: Two Souls is woven from opposites. Despite all its silly attempts to appear deep, it still manages to be enjoyable. It will tell you about the modest and beautiful nuances of the life of its extraordinary heroine, but it won’t tell you anything important about life or death. When Beyond focuses on something more personal, everything is fine, but as soon as the game expands its focus, it falls apart.

The greatest paradox of this game is that in some aspects it surpasses most high-budget games, but it struggles with elements that work perfectly in less ambitious projects. If David Cage abandons his worship of precious Hollywood and looks at the more grounded possibilities of interactive storytelling, he might be able to grasp an idea that could become a true masterpiece. But for now, we have Beyond: Two Souls: quiet, gentle, and smart – until it starts behaving loudly, rudely, and foolishly.

It is rare for me to struggle with rating a game and to be so concerned about who should play it and who should not. I will only say that I know what bad ratings can be given to decent games that were not understood.

Share

Discuss

More Reviews