SOMA Review

From horror, it is not customary to expect depth, pretentiousness, and morality. Fear is not a very complex feeling, and to maintain it, it is usually enough to push a helpless player into pitch darkness, throw something unpleasant at them for company, and create a suffocating atmosphere with a couple of sharp sounds. This is what every first horror game on Greenlight does, and before them, Frictional Games did the same in their Amnesia: The Dark Descent.

Let’s be honest, what were you most afraid of in “Amnesia”? I’m ready to bet on those disproportionate freaks with sagging jaws, lurking in the darkness. Or the piercing cries, moans, and rustling, again, coming from the darkness. However it may be, in the impenetrable haze of the castle, fear was palpable and animalistic – a fear that hindered thinking with its presence.

SOMA, as befits a more mature project, takes a completely different approach. They didn’t abandon Frictional’s favorite techniques, but oh my god, putting the story at the forefront instead of straightforward monsters – that was unexpected and, dare I say, right.

Although at first everything seems to be within familiar boundaries. Simon Jarrett, an employee of a bookstore somewhere in Toronto, finds himself far beyond his hometown and time – more precisely, on the underwater station Pathos-II of the year 2103. Total abandonment and bloody traces on the floor suggest that warm reception is not to be expected, nor any explanations for what happened. Isn’t this reminiscent of Daniel’s amnesia from The Dark Descent? Well, at least in the sense that it’s not an ordinary horror circus in a futuristic setting, but a monumental science fiction story with a sudden profound subtext.

But enough details – it’s best to figure out what’s happening at Pathos-II, where the station’s inhabitants have gone, and why the robots consider themselves alive, on your own. And it’s not so much about the twists and turns of the plot, which undoubtedly intrigue, but about the sensations of gradually realizing the reality. It is crucial to be in complete ignorance here, so that it smoothly transitions into confusion and provokes questions bigger than the standard “what is happening?”.

Behind the striking facade of SOMA lies a whole complex of philosophical musings on various topics. About what consciousness is and whether it can exist without a body, about artificial intelligence, loneliness, death, ultimately. Esteemed science fiction writers have been dedicating their works to all of this for decades, but in the gaming industry, such a massive statement appears, perhaps, for the first time. Throughout the narrative, the authors allow themselves to doubt the factors that determine one’s identity, distort the understanding of reality, challenge familiar moral norms, and through interactive form, they also urge us to do the same.

And this is much scarier than any jump scare or patchwork monster.

They truly frighten when nothing is crashing anywhere and no one is dripping black slime from the ceiling – when there is time to contemplate. Doubts, assumptions, contradictions, and an abundance of categories literally tear your mind apart, which somehow escape attention in everyday life but do not appear in games of this kind in principle. Some motifs are not even directly expressed, but they resonate with the main idea and inevitably arise in a spontaneous cloud of thoughts. Needless to say, all these “what if…” scenarios crank up the level of internal anxiety to the maximum, and fear takes on some kind of… global character, so to speak.

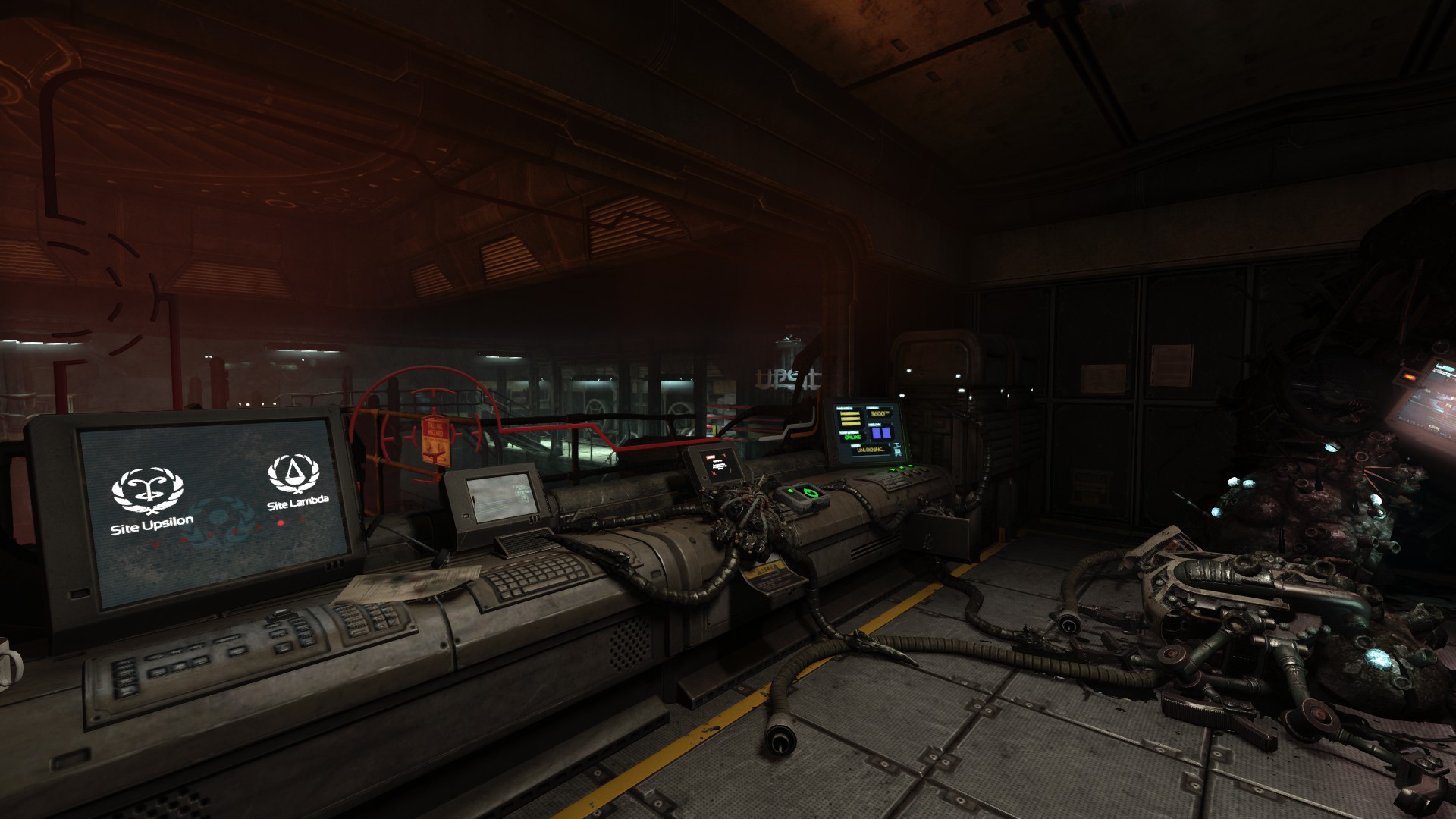

The atmosphere also contributes to this. Depressingly silent interiors often do not allow you to concentrate on anything else but your own thoughts. Sometimes in the compartments, you can find an electronic archive or catch a short flashback, but such a retrospective of the fate of the station’s personnel and humanity as a whole only weighs heavily with relentless melancholy.

Not least of all, the identification with the protagonist influences the emotional impact of the above. Fortunately, Simon is not Gordon Freeman and behaves like a normal person: he wonders, gets angry, fears, and even jokes if the situation allows. Despite his clearly defined character and backstory, all of his experiences are projected onto the player in an astonishing way. It is not desirable to play an abstract role here – every dilemma forces you to answer the question: “What would I do in such a case?”. And if the situation forces him to commit a murder, albeit indirectly, do not doubt that the burden of responsibility for what has been done will fall entirely on your shoulders.

This is Catherine. She is almost your only interlocutor throughout the entire game. And yes, she is in the computer.

As mentioned earlier, Amnesia couldn’t do without its quirks, and when, ahem, the ghosts of the past make themselves known, SOMA presents itself in the most, perhaps, unfavorable light. Encounters with enemies, which The Dark Descent relied on, seem completely out of place here and resemble more of an attempt to avoid those who don’t like Frictional’s games without distorted creatures.

But an interesting concept is visible. The old concept has clearly been tried to diversify through unique individuals: humanoid blisters occasionally roam the station corridors, robots with glowing growths, and so on – and each of them has a certain characteristic that theoretically dictates the rules of the game. The problem is only that the long legs of the main character, which act as the ultimate weapon in any confrontation, still dictate them.

You can still escape from anyone and anywhere – this is allowed by the circular layout of most levels and the silly AI of monsters who lose interest in the chase in a matter of seconds. Over the almost three centuries that separate the events at Pathos-II from the horror of Brennenburg Castle, the methods of fighting enemies have not changed at all, and this is quite strange. What’s the use of a creature with heightened hearing if it doesn’t react to a book thrown into a corner of the room? Why are all these lockers here if you can’t hide in them? How does this evil manage to open locked doors, finally?

It won’t be possible to have a conversation with such people – brutes only know the language of beatings.

What’s even more interesting is that the game doesn’t really hinder you from bypassing enemies while sprinting. Dying in SOMA is ridiculously difficult because the local mutants only give you a slap in the face upon direct contact and then run away to the other end of the location with a triumphant cry. The protagonist may lose some agility from this, but he won’t be too upset – without “recharging,” Simon can withstand three or four of these punches, which is more than enough to get through a challenging section.

In short, a major repair would definitely not hurt the stealth mechanics, especially since there are plenty of examples to follow – the same ones have accumulated enough. Alien: Isolation There is something to borrow. Fortunately, the developers did not abuse dubious shortcuts and preferred to dedicate a large part of the gameplay to simple puzzles and exploration.

The overall impressions make me remember the second part of Amnesia There is almost no senseless horror in it – mainly the effect is achieved through plot revelations, a dense atmosphere, and excellent sound. which we wrote about earlier But where A Machine for Pigs gravitated towards static corridor storytelling, close to interactive novels, SOMA still strives to enrich the idea with a corresponding gaming experience. Such a symbiosis is new to horror games, so it is not surprising that it didn’t turn out perfectly the first time.

SOMA is a testament to the growth not only of the genre, but also of games as a whole. By using interactivity as an artistic tool, Frictional took on a series of serious questions and presented them in a unified work with dignity. Perhaps the project came out slightly less polished than it should have been, and the understanding of fear here goes against the expectations of the masses, but as long as the list of works of art among such entertainment is replenished with gems like this, there is no need to worry about the industry.

Share

Discuss

More Reviews